Central bank governors are not normally known for being outspoken or critical of prevailing economic policies. Not the case, it seems, for Mark Carney and David Dodge, former governors of the Bank of Canada.

Mr. Dodge, in a report for the legal firm Bennett Jones, has recently warned against premature fiscal tightening in the current economic climate. Indeed, he and his coauthors advocate an expansion in infrastructure spending — in ports, roads and transit systems — among other things. Even though this will mean continuing fiscal deficits, they say that “in the current environment of low long-term interest rates, fiscal prudence does not require bringing the annual budget balance to almost zero immediately”. Such counsel flouts the current policy stance of the federal Conservative government, which is to eliminate the budget deficit next year.

Since 2008, policymakers have debated how to prevent the financial crisis from precipitating a second Great Depression. In 2008-09, the Group of 20 (G20) agreed to inject a considerable amount of fiscal stimulus to maintain aggregate demand. At the same time, central banks have implemented interest-rate reductions and provided enormous amounts of liquidity to their banks to maintain confidence and to prevent seizure in payments systems.

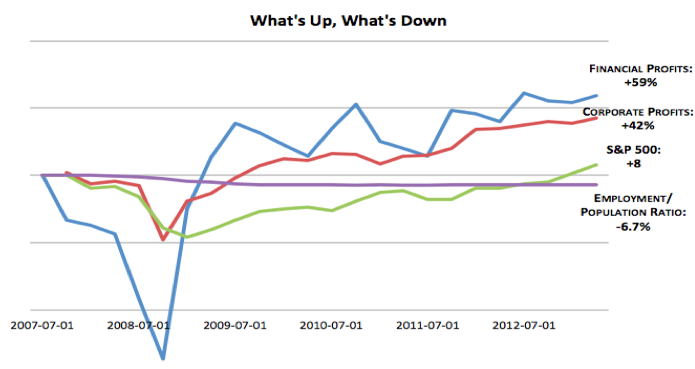

Today, it is clear that these countercyclical initiatives helped to avert a global economic catastrophe. But they did not foster economic recovery. By 2010, the revival of financial and corporate profits were mistakenly taken as an indicator of the “green shoots” of economic recovery, even though employment continued to languish below pre-crisis levels.

(Source: Derek Thomson, The Atlantic)

This gave fiscal conservatives a pretext to unwind the fiscal deficits occasioned by the extraordinary stimulus measures. There were calls for fiscal consolidation — meaning spending reductions rather than tax increases — at the G8 and G20 meetings held in Canada that year. Balancing the budget became the order of the day. As a result, the recovery has stalled and advanced economies have endured what is now called the Great Recession, with unemployment and growth languishing at around pre-crisis levels.

Progressive economists have criticized what amounts to a renunciation of the fiscal stimulus that so successfully averted depression in 2008-09. This happened precisely because fiscal conservatives wished to avoid legitimizing a return to Keynesian policies, in which government spending plays a key role in fostering economic stabilization and growth. Instead, they believe fiscal consolidation via expenditure cuts is a prerequisite for the recovery by creating room for business and consumer spending.

However, instead of stimulating business investment, corporations are merely sitting atop a $630 billion mountain of liquidity (dubbed by former Bank of Canada Governor Mark Carney as “dead money”).

At the same time, it is clear that fiscal conservatives are not averse to monetary stimulus, which has remained in place, in the hope that near-zero interest rates would encourage borrowing, consumer spending, and business investment. To the extent that consumer borrowing has underpinned housing sales and construction such measures have had a positive impact. However, in Canada the underside of the housing revival has been increased consumer debt, house prices that are increasingly unaffordable (as a recent OECD report pointed out) and the spectre of a bursting bubble and debt distress similar to that in the United States in 2007-08.

Moreover, low interest rates have fuelled a search for yield, which lurks beneath the extraordinary “recovery” of the stock market since 2012. And with interest rates approaching zero, there is nowhere for further stimulus to go — unless central banks wish to introduce negative interest rates, that is, by levying interest charges on depositors. (Indeed, the European Central Bank has just introduced such rates for the first time. Whether this will induce depositors to go out and spend, or merely withdraw their funds in cash to stuff under their mattresses, remains to be seen.)

What is wrong with this picture? As anyone who has studied basic macroeconomics should know, expansionary monetary policy (interest rate changes that increase the money supply) doesn’t work well in combating recessions. Restrictive monetary policy is far more effective in controlling inflation and excess demand, as we saw in the 1980s with the “Volcker shock”. In contrast, expansionary fiscal policy is better at fighting recessions by injecting spending directly into the economy, as we saw with the stimulus measures of 2008-09.

Better yet is fiscal and monetary policy working in tandem to stabilize the business cycle. Unfortunately, what we now have is monetary stimulus going it alone — the macroeconomic equivalent of one hand clapping.

There is another interesting strand to the recent debate on the role of fiscal policy — or more specifically, on the limits of deficit spending. Thanks to Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, two U.S. economists who have written extensively on debt and financial crises, a belief has arisen that once the public debt level rises to a critical point through the accumulation of fiscal deficits, it has a negative impact on economic growth. In a 2010 paper they claimed that debt levels above 90% of GDP were associated with dramatically worse growth outcomes. While their claims have been discredited by critics who discovered data-entry errors in the analysis, others have also found that debt levels above 90% of GDP have exerted a drag on growth.

These arguments play powerfully into the hands of fiscal conservatives who seek evidence on which to base their push for fiscal consolidation. However, a recent paper published by the IMF reviewed the evidence from 24 countries over a long period (over a century) and concluded that “there is no simple threshold for debt ratios above which medium-term growth prospects are severely undermined”. The IMF study cautioned that their conclusion should not be taken to mean that debt levels are unproblematic.

In the current moment, the question for Canadian policymakers is: why should deficits be incurred over the next few years rather than eliminated next year, as the Conservative government intends?

To return to the report by Dodge and his colleagues, the argument really turns on how to get the economy growing again. They point out that Canada’s productivity performance has suffered relative to the United States, particularly since 2003, which along with appreciation in the value of the Canadian dollar, has led to an erosion of competitiveness and weak economic growth. To foster enhanced productivity, and hence growth, they recommend investing in infrastructure and human capital development.

Infrastructure investment, in particular, will require large expenditure outlays, and continuing fiscal deficits. However, they assert that what is important is not the absolute size of the debt or deficits, but the public debt to GDP ratio. The latter will decline as long as the fiscal deficit as a percent of GDP, and the interest rate on debt, are less than the nominal rate of GDP growth. In the current low-interest rate environment, which is likely to persist for at least two more years, they argue that the government really must seize the opportunity to foster a more vibrant recovery and reduce unemployment.

It is evident that Dodge and his colleagues give some credence to the notion that the debt to GDP ratio is important, or at any rate should be kept from rising. Accordingly, they occupy a middle ground between fiscal conservatives who are hell-bent on deficit elimination and debt reduction, and those who would put more weight on economic recovery and lower unemployment — even if the debt to GDP ratio rises.

At any rate, it is refreshing to hear pragmatic economic policy advice from a respected former senior official of the federal government (Dodge was Deputy Minister of Finance before going to the Bank of Canada). The real dragons to be slain are not deficits and debt, but the dismal economic prospects confronting millions of Canadians seeking stable, well-paying jobs.

Roy Culpeper is the former President of the North-South Institute and currently a Senior Fellow of the University of Ottawa’s School of International Development and Global Studies, and Adjunct Professor at the Carleton University School of Public Policy and Administration.

Photo: dneuman. Used under a Creative Commons BY-SA 2.0 licence.